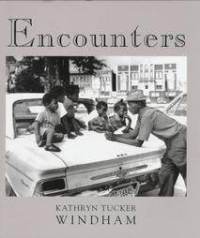

Kathryn Tucker Windham, who died Sunday, was well-known as a story-teller and an author. Less well-known was her considerable talent as a photographer. Among Mrs. Windham’s favorites of her own books was Encounters, a 1998 collection of photos and essays edited and published by NewSouth editor Randall Williams. In the introduction to that book (now sadly out of print), Williams wrote:

Kathryn Tucker Windham, who died Sunday, was well-known as a story-teller and an author. Less well-known was her considerable talent as a photographer. Among Mrs. Windham’s favorites of her own books was Encounters, a 1998 collection of photos and essays edited and published by NewSouth editor Randall Williams. In the introduction to that book (now sadly out of print), Williams wrote:

In an essay in her 1996 book, Twice Blessed, Kathryn Tucker Windham tells how she got started taking pictures as a child in Thomasville, Alabama. She got up before daylight one day in the summer of 1930 to be first in line at the People’s Drug Company to receive one of the half-million Brownie cameras that Eastman Kodak was giving away to twelve-year-olds for the company’s fiftieth anniversary. Her conscience, she wrote, always troubled her that she never properly thanked Kodak for that first camera.

Over the years her cameras have included a Speed Graphic, a Yashica, a Cannon, and a Pentax. But the Brownie was the beginning, and this book includes several images (“First Airplane Ride,” “Basket Maker,” “Uncle Hiram Davis,” and “Woman With Spinning Wheel”) made with that camera, a git that led to her life-long interest in photography.

As with many of the interests that have filled her seventy-nine years, it is hard to know how to describe her relationship to photography. She has never been a news photographer in the sense that her primary job was to take pictures, yet in her journalism and later in her folklore the camera was an ever-present and always important tool. She knew how and when to use it, too: plenty of photojournalists would give their eyeteeth to cover a fire and come back not with another routine picture of a burning house but with the portrait of two boys snatching laundry off a clothesline (“Saving the Wash”) as the rest of their family’s possessions go up in smoke nearby. On the other hand, photography seems never to have been merely a hobby with her. Clearly, she has taken photographs for enjoyment, but then she does everything for enjoyment, which is part of what makes her such an effective storyteller and makes her pictures so inherently satisfying to look at. Nor has she ever styled herself as an artist, though the framing and composition of some of her images are as strong as in images by her Mississippi neighbor Eudora Welty and by a younger fellow Alabama Black Belt native, William Christenberry, both of whom are widely celebrated observers of the same rural Southern scenes upon which Kathryn Windham has trained her succession of cameras over the decades.Her photography has not been as well-recognized as her writing and her storytelling, but in 1993 she was honored with an exhibition of twenty-eight of her pictures at the Huntsville, Alabama, Museum of Art. The curator, Frances Robb, a photographic archivist and historian, observed that Mrs. Windham’s “…stories are rich in descriptive detail and narrative incident. So are her photographs. Her vision includes archetypal images — whittler, scarecrow, abandoned tenant house — and unexpected landmarks: a crooked church, a portrait gravemarker sculpted in concrete, factory-reject toy horses lining a rural driveway. All record the enduring human presence in a changing yet timeless South…”

In the present volume, readers have the best of both world: her photographs and her stories, recalled from notes and memory from the time images were made.

Kathryn Tucker Windham grew up in Thomasville, Alabama. She graduated from Huntingdon College in 1939 (the college awarded her an honorary Doctorate of Literature in 1979), married Amasa Benjamin Windham in 1946, and had three children before being widowed in 1956.

A newspaper reporter by profession, her journalistic career (with the Alabama Journal, the Birmingham News, and the Selma Times-Journal) spanned four decades, beginning in the shadow of the Great Depression and continuing through the Civil Rights movement, which she observed at the ground level in her adopted home town of Selma.

In the 1970s, she left newspapering and worked for a time as a coordinator for a federally funded agency for programs for the elderly. Meanwhile she continued to write, take photographs, and tell stories. The storytelling was an outgrowth of her 1969 book, 13 Alabama Ghosts and Jeffrey, written with her former college English teacher, the late Margaret Gillis Figh. More volumes of ghost stories, folklore, recipes, and essays followed; Encounters is her nineteenth book. Her reputation as a storyteller spread after she made (in 1974) her first of many appearances at the annual National Storytelling Festival. Then, in the 1980s, she became a commentator on WUAL, the public radio station affiliated with the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa. This led to thirty-three appearances over an eighteen-month period on National Public Radio’s All Things Considered, which introduced her to an even larger audience.

She has written, produced, and acted in a one-woman play, My Name is Julia, about pioneering social reformer Julia Tuttweiler, has narrated several television documentaries, and is a regular interviewee for nation and international journalists visiting Alabama in search of the Old or the New South. It is a testament to the good humor, keen intelligence, and life-long curiosity of one of the region’s best known public citizens that she can guide the visitors unerringly to either mythical place.

Kathryn Tucker Windham’s latest book was her memoir Spit, Scarey Ann, and Sweat Bees. Visit the NewSouth Books blog tomorrow for more remembrances of Kathryn Tucker Windham.