It is tempting to lament that we live in dark and troubling times, but then humankind always has. “I am a man of constant sorrow” is more than a mournful lyric; it’s practically a summary of world history. And at a moment when one troubled soul takes the lives of other souls in a dark movie theater, when a corporation like Caterpillar increases executive salaries because of $4.9 billion in earnings last year but simultaneously seeks wage concessions from its employees, when states like Alabama and Arizona seek to criminalize simply helping out someone who might be an undocumented worker . . .

It is tempting to lament that we live in dark and troubling times, but then humankind always has. “I am a man of constant sorrow” is more than a mournful lyric; it’s practically a summary of world history. And at a moment when one troubled soul takes the lives of other souls in a dark movie theater, when a corporation like Caterpillar increases executive salaries because of $4.9 billion in earnings last year but simultaneously seeks wage concessions from its employees, when states like Alabama and Arizona seek to criminalize simply helping out someone who might be an undocumented worker . . .

Well, one could go on with the depressing litany, but it is helpful to be reminded, as Charles Hoffacker did on the Sunday after Independence Day, that “our nation has had Uriah moments, reasons for honest repentance. We have had Goliath moments as well, causes for celebration. Our country is designed not to be an empire, and not to be a church, but to be a commonwealth, an experiment in democracy.”

Hoffacker, pastor of St. Christopher’s Episcopal Church in New Carrollton, Maryland, is an old college friend of attorney Will Campbell of Lancaster, Pennyslvania, who is an old friend of NewSouth’s and one of our small but valued stable of volunteer proofreaders and manuscript readers. Hoffacker forwarded his sermon to Will, and Will forwarded it to us, and we have now forwarded it to you. Reading it made us feel more hopeful; we hope it works the same magic for you.

GOLIATH MOMENTSÂ by Charles Hoffacker

A sermon preached at St. Christopher’s Episcopal Church, New Carrollton, Maryland, on July 8, 2012

(Readings: 2 Samuel 5:1-5, 9-10;Â 2 Corinthians 12:2-10;Â Mark 6:1-13)

“David was thirty years old when he began to reign, and he reigned for forty years. . . . David occupied the stronghold, and named it the city of David. David built the city all around from the Millo inward. And David became greater and greater, for the Lord of hosts was with him.â€

There is something strong and imperial and complete about these words from today’s first reading. They constitute a summary about the reign of King David. They claim a divine sanction for David’s success. But they leave out much more than they contain. The story of David, which stretches through many chapters of scripture, is far more human and horrible and glorious than this scrap of royal chronicle.

At the Palmer Art Museum in University Park, Pennsylvania, is an oil painting from seventeenth-century Italy that depicts David with the head of Goliath.

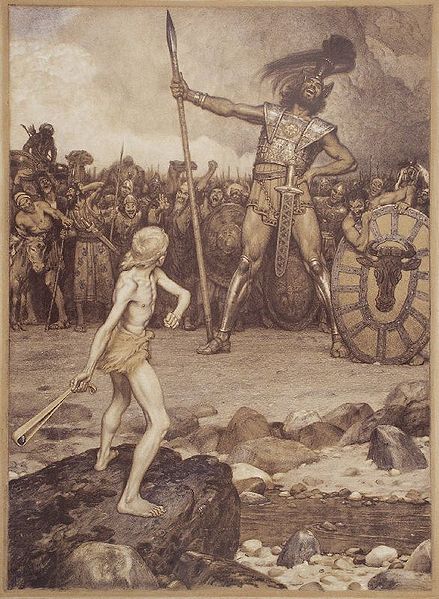

The artist Girolamo Forabosco shows us David, not as a king, but as a shepherd, a teenager, the youngest of all the sons of Jesse. He has killed the giant warrior Goliath with a slingshot, cut off his head, and now carries that monstrously huge head on one shoulder, holding it in place with both hands as though it were a watermelon.

Here David embodies the unconscious grace of youth. In contrast, the head of Goliath, eyes closed, shows the tinctures of death, with a great red bruise on the forehead marking the spot hit by David’s fatal stone.

What is most notable about this painting is the expression on young David’s face. He does not display the exuberant triumph of, for example, a football player who has just won the championship game. No, young David appears lost in thought; apparently he is aware that this remarkable success has brought an end to his simple existence. The life that awaits him — many more heroics, forty years as king — will be heavy with complexities.

The young David did what Saul’s entire army did not. He kills the monstrous enemy champion, Goliath of Gath. He does not rely on the finest armor and weapons, but kills the giant with a stone from a slingshot. The Philistine looks powerful, but proves to be weak. David the shepherd boy looks weak, but proves to be powerful. And scripture all but shouts at us how God is at work in the powerful weakness of young David.

David gains power of a more conventional kind. His record as king turns out to be decidedly mixed. Sometimes he discerns and does what is right. At other times he abuses his power and commits heinous crimes. Perhaps the worst episode involves committing adultery with Bathsheba and then setting up the murder of Uriah, one of his loyal soldiers. If God was with David, as today’s reading claims, then at times God must have been present with him in judgment.

The saga of David is one of the great stories in biblical literature. He is a character who haunts western culture. But let’s go a step further. I believe David — shepherd boy and king — also haunts western politics. On this Sunday after our holiday of national independence, we would do well to remember that over the last two centuries and more, our country has had its Goliath moments and its Uriah moments.

Sometimes our weakness has been revealed as strength. And sometimes our strength has been revealed as weakness. If we ask God to bless our nation, then we must remember that this blessing comes as both mercy and judgment. The living God is nobody’s national mascot, but demands that we do justice, and love mercy, and walk before him in humility.

Our country has had its Uriah moments when out of arrogance and blindness of power, we have betrayed trust and squandered opportunity and offended God who has sent his prophets to speak truth against lies.

Our country has had its Goliath moments when out of weakness that refuses to be afraid, we have toppled giants and beheaded them so that, however momentarily, God’s reign has been tangible.

And because our country is no monolith, but a combination of persons and factions, often the Goliath moment and the Uriah moment have been the same moment. We the people have shown simultaneously both the worst that is in us and the best. Together we behave as David did.

And so there is a reason if our national countenance, like Forabosco’s portrait of David, looks perplexed even at a moment of victory, for our national life is full of perplexities. We killed one Goliath at the time of the Revolution, when thousands of young Davids encamped in places like Valley Forge, and it has been, perhaps inevitably, a mottled saga ever since.

I will not focus on the Uriah moments except as background for when one Goliath or another has been slain. But for a sad and scholarly accounting of many Uriah moments in our national life, turn to Howard Zinn’s extraordinary work, A People’s History of the United States. I confess I did not finish reading this book, for its accounting of sorrows is relentless.

Instead I wish to put before you three moments out of countless others when out of weakness Americans have found strength to slay some threatening giant.

* Sometimes Goliath is despair and David hurls a stone of hope against him.

The year was 1850, the place Fanieul Hall in Boston. The great Frederick Douglass was speaking. In the course of his address, he grew more and more agitated, more and more despairing, finally saying that he saw no possibility for justice for people of African descent outside of violence and bloodshed.

Douglass sat down, and the audience fell into a tense hush. Sitting in the very first row was Sojourner Truth, a woman who knew the evils of slavery from personal experience, having been sold four times. She rose, and her deep and commanding voice spoke a sentence heard throughout the auditorium. “Frederick, is God dead?â€

* Sometimes Goliath is weariness in well-doing and David hurls a stone of solidarity to kill him.

An unfinished chapter in American history concerns the labor movement and its struggles against oppressive conditions.

A most unlikely David arose in the person of a poor Irish widow named Mother Jones. Some spoke her name with contempt, but she was a mother to the great masses who labored in the dark coal mines or worked for sixty-five hours every week in the mills.

In the 1890s she served as an agitator for the United Mine Workers where her fiery speeches would move men and women to tears and compel them to action. In Colorado she approached a machine gun poised to open fire on a line of demonstrators; she placed her hand on the barrel, turned it to the ground, and then walked on by.

She once told a congressional committee, “My address is wherever there is a fight against oppression.â€

* Sometimes Goliath is a fear of strangers and David hurls a stone of acceptance, a stone of welcome, to kill him.

It was a great day when these words of invitation composed by Emma Lazarus were first displayed on the Statue of Liberty there in New York Harbor for all the world to see:

“Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door.â€

Words of welcome to the weak and rejected. An invitation for them to grow strong in a commonwealth whose only nobility is to be a nobility of character.

Whether our families came here on slave ships or jumbo jets, this invitation is meant for us and our children, and we are to offer it as well to others. Each new arrival is not a threat, but comes bearing gifts meant to build up our common life.

Our nation has had Uriah moments, reasons for honest repentance. We have had Goliath moments as well, causes for celebration. Our country is designed not to be an empire, and not to be a church, but to be a commonwealth, an experiment in democracy.

God is with us, as God is with all nations and peoples of the earth. The choice remains ours, however, whether we will offer God Uriah moments to judge or Goliath moments to bless. Goliath moments– when strength arises out of weakness, despair gives way to hope, weariness is replaced by solidarity, and fear dissolves in the face of acceptance and welcome. There are Goliath moments still to come in our nation’s future.