Interest in the ground-breaking African American architect Robert R. Taylor continues to grow after the publication of Professor Ellen Weiss’s detailed biography of Taylor, and articles including two in Architect magazine.

Interest in the ground-breaking African American architect Robert R. Taylor continues to grow after the publication of Professor Ellen Weiss’s detailed biography of Taylor, and articles including two in Architect magazine.

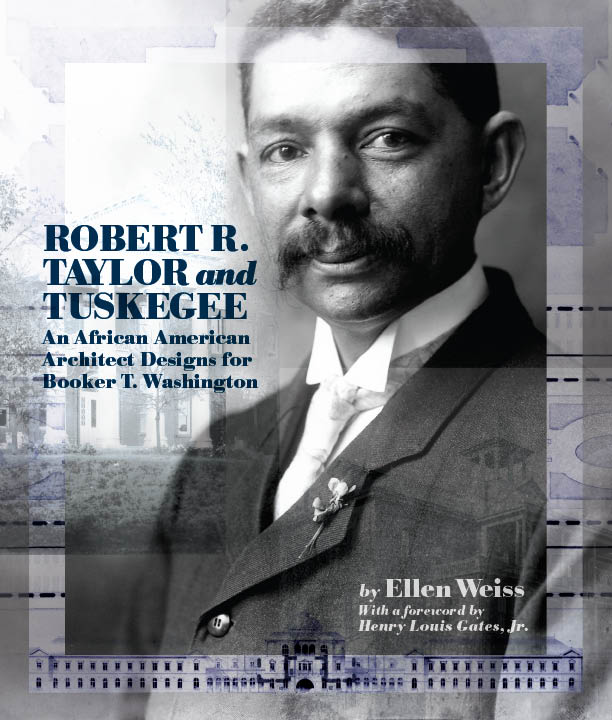

Weiss’s Robert R. Taylor and Tuskegee recounts Taylor’s life, side by side with striking photographs of Taylor’s architectural accomplishments as the first classically trained African American architect. Taylor was MIT’s first African American graduate in 1892, and soon after Booker T. Washington recruited Taylor to teach and design the campus of Washington’s Tuskegee Institute.

“He had a classical French training at MIT,” Weiss told WWNO’s Fred Kasten on his The Sound of Books program, “and this shows in many overt ways like the correct use of columns, a very sensitive approach to proportion, to thickness of walls, to all the tactile and visual qualities of architecture and its material.” Washington wanted the architecture of Tuskegee Institute to reflect to both the outside world and to Tuskegee’s own students the capabilities of African Americans.

Writing in the “AIAVoices” column in Architect magazine, Weiss explains that “the campus (built by black carpenters and masons who could draw a little) was already 10 years old when Taylor arrived. One of Taylor’s predecessors was Booker T. Washington’s brother, who had some construction experience. But these buildings didn’t have the eloquence or character of buildings designed by a classically trained architect. Washington saw the difference. He had been trained at Hampton Institute in Virginia, for which Richard Morris Hunt designed several buildings. Washington would have seen Hunt’s work and he understood what architecture could mean for a sense of place.”

In a review of Robert R. Taylor and Tuskegee, Ben Steelman of Star News notes that “most intriguing are the hints Weiss finds of a longstanding friendship between Taylor and a fellow MIT alumnus from Wilmington, Hugh MacRae. MacRae’s reputation has suffered in recent years. H. Leon Prather (in We Have Taken a City) and Philip Gerard (in his novel Cape Fear Rising) have painted him as one of the bloodthirstiest plotters of the 1898 coup, and he did leave the land for the park that bears his name to the white residents of New Hanover County. Yet as early as 1918, Taylor was requesting that MacRae be invited to a Tuskegee commencement, noting that his interest in farm colonies had turned from transplanting foreign workers to employing ‘Negro men.’ During the Depression, Taylor and MacRae would together propose a program of Southern rural homesteading as a remedy for widespread African-American unemployment and poverty.”

Steelman goes on to praise Weiss’s book, including that Weiss “adds an important footnote to Wilmington history and to our understanding of the Jim Crow era.”

In a Q&A that also appeared in Architect, Weiss suggests that Taylor’s most important or influential building was the Tuskegee Chapel. “At its dedication, a New Yorker said it was a ‘cathedral in the Black Belt,’ where blacks and whites could stand equal before God. The chapel burned down in 1957.

“The Carnegie Library exterior remains, even though its interior has been gutted. Its iconic portico asks us to consider the meaning of such Classicizing assertiveness, an emblem of authority for centuries, when it appears in a black school in the Deep South just as Jim Crow was locking in. In 1901, the year the library was built, the Alabama constitution denied the vote to most African-Americans. Meanwhile, Southern whites were threatening Washington’s life and the school’s existence for all sorts of effrontery, even as some Northern blacks thought the principal was knuckling under to the racists and selling out his people. Perhaps Taylor and Washington were asserting racial parity in the safer medium of design.”

Finally, in an Encyclopedia of Alabama entry about Robert Taylor written by Weiss, she includes an unusual fact of Taylor’s death: “In December 1942, while visiting family in Tuskegee, he collapsed in the chapel he had designed and built and died on December 13, in the hospital he had designed and built. He was buried in Wilmington’s Pine Forest Cemetery, which his father had helped found.” Taylor, Weiss writes, “had a prolific and wide-ranging career.”

Read more about Robert Taylor from Star News, Architect magazine, and the Encyclopedia of Alabama; Fred Kazen’s The Sound of Books is also available for listening online.

Robert R. Taylor and Tuskegee: An African American Architect Designs for Booker T. Washington is available direct from NewSouth Books, Amazon, or your favorite bookstore.