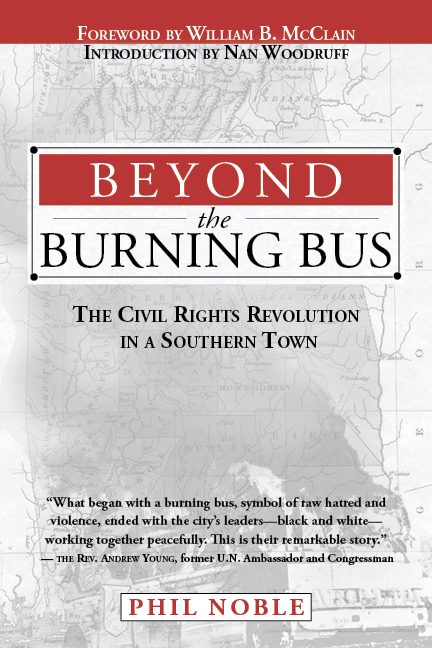

The February 2015 edition of the Episcopal Journal offers a full-page feature on Reverend Phil Noble’s book Beyond the Burning Bus: The Civil Rights Revolution in a Southern Town, and the events in Anniston, Alabama, that lead to the city’s formation of the Human Relations Council. With racial tension in the news and resurgent interest in the Civil Rights Movement with the release of the movie Selma, Noble’s first-hand account of the violence and reconciliation in his town remains required reading.

The February 2015 edition of the Episcopal Journal offers a full-page feature on Reverend Phil Noble’s book Beyond the Burning Bus: The Civil Rights Revolution in a Southern Town, and the events in Anniston, Alabama, that lead to the city’s formation of the Human Relations Council. With racial tension in the news and resurgent interest in the Civil Rights Movement with the release of the movie Selma, Noble’s first-hand account of the violence and reconciliation in his town remains required reading.

The Day1 religious blog also posted an excerpt from Noble’s book.

Noble was minister of Anniston’s First Presbyterian Church in 1961 when the Freedom Riders arrived in Anniston on their mission to end segregation. A mob surrounded their bus, and broke the windows, dragged out and beat the passengers, and set the bus on fire. In his book, Noble recalls that the reaction from the Anniston community was mixed. “Anniston had the capacity for racial violence that was equal to any other community in the South,” Noble writes. “Some felt the horror of the tragedy. Others said, ‘It’s too bad, but they got what they deserved.'”

The violence so alarmed Anniston’s religious, business, and political communities that they created the biracial Human Relations Council, with Noble appointed as the council chair. As the Episcopal Journal recounts, from Beyond the Burning Bus, Noble’s committee would vary their meeting times and locations for fear of those who disagreed.

“We would set a date and time for our next meeting, and then a half-hour or hour before the meeting I would call and tell members the place [to meet],” Noble writes. The group alternated between such locations as a church, the YMCA, a bank’s board room or the Chamber of Commerce. Because white and black members of the council were strangers to each other, Noble describes how he talked about the need for respect and for a sense of trust in how they dealt with one another. Eventually, Noble succeeded.

“The minister at Grace Episcopal Church told one of his members who was to serve later on the Human Relations Committee that we had gotten to a first-name basis, black and white,” Noble writes. “The member was indignant that there would be such familiarity, that blacks would call whites by their first names.”

Deeply entrenched customs pervaded the South then, and segregation still ruled. The council had mixed results in attempting to desegregate the city’s public buildings without incident or violence. An attempt to integrate the public library, undertaken with the approval of the library board, resulted in the beating of two black council members by a group of about 50 whites on the library steps. As the two attempted to flee by car, one was wounded by gunfire.

It is worth noting that, while the mayor and newly elected town commissioner supported the work of the biracial council, the police chief and most members of his force did not. Noble describes how thin a line the council members trod. “The black community thought we were going too slow, and the white community thought we were going too fast,” Noble says. “Our churches were no exception.

“One of the reasons for the success we had was that we were able for the most part to maintain that balance. We made enough progress so that the black community did not feel completely frustrated, and, at the same time, the progress was gradual enough so that the white community accepted it.”

Read the full Episcopal Journal book review at the link. You can also read an additional excerpt from Beyond the Burning Bus at Day1.org.

Beyond the Burning Bus: The Civil Rights Revolution in a Southern Town is available from NewSouth Books or your favorite bookstore.