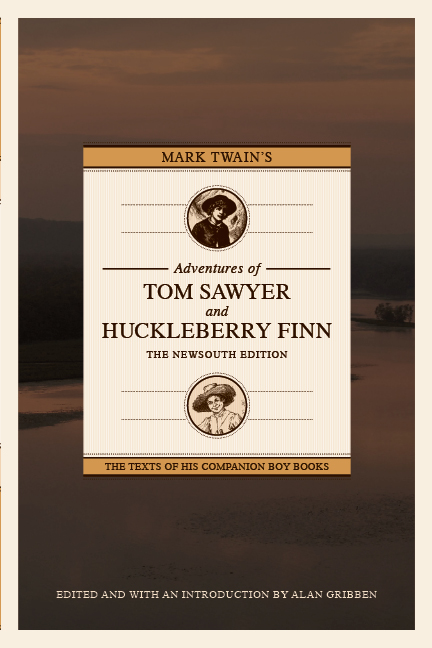

NewSouth Books appreciates all the attention and thoughtful debate generated by our publication of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, edited by Dr. Alan Gribben. We are still taking in the unprecedented media coverage of the book, and reading closely the comments and letters we’ve received.

NewSouth Books appreciates all the attention and thoughtful debate generated by our publication of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, edited by Dr. Alan Gribben. We are still taking in the unprecedented media coverage of the book, and reading closely the comments and letters we’ve received.

While it would be difficult to link to all the coverage of the book, here’s a selection that stuck out to us over the course of last week, beginning with a retrospective from Publishers Weekly:

“NewSouth Moves Ahead with Controversial ‘Huck Finn,'” Marc Schultz, Publishers Weekly:

Since Monday, when PW first reported the publisher’s plans to release Twain’s most celebrated and challenged works without the “hurtful epithets†that have caused it to be dropped from school curricula, the story has generated enormous interest in both new and old media outlets — on Tuesday night, the report from ABC’s Diane Sawyer focused more on the Twitter debate than the who or why of the story.

“Cutting N-word from Twain is not censorship,” Boyce Watkins, CNN

Let’s be clear, Gribben’s actions do not represent censorship, at least not in its purest form … It’s not as if Gribben is asking that all original copies of the text be burned. He is not following the lead of the Chinese government and attempting to block websites that make reference to the book … He is expanding the freedom of teachers and parents to choose a version of the book that they might find more acceptable for children of a certain age.

The notion that any form of filtering, in any context, for any age group, is unethical is not only exceedingly idealistic, it is disconnected from reality. No matter how cherished a film or song might be, work presented to students in public school is going to be screened to determine whether it matches the age group for which the material is being presented.

Yes, our nation needs an honest conversation on race. That conversation shouldn’t start and end with “Huckleberry Finn.” In fact, the urgency with which some defend the use of this book as a tool for teaching racial history reflects our desperate and unfulfilled need to address the atrocities of slavery.

Keith Olbermann, Countdown with Keith Olbermann:

I despise censorship … on the other hand, it’s madness that Huckleberry Finn is essentially off-limits to anybody until college or later.

“Huckleberry Finn gets self-censored, loses ‘n word,'” David Rosenthal, Baltimore Sun:

I’m not big on censorship, but this word is so weighted that it gets in the way of a true discussion of the merits. Any teacher who assigns the new version should be required to explain the self-censorship. That way, at least, the tough prose won’t be completely white-washed.

“New edition removes Mark Twain’s ‘offensive’ words,” Phil Rawls, Associated Press:

The book isn’t scheduled to be published until February, at a mere 7,500 copies, but Gribben has already received a flood of hateful e-mail accusing him of desecrating the novels. He said the e-mails prove the word makes people uncomfortable. “Not one of them mentions the word. They dance around it,” he said.

Gribben, a 69-year-old English professor at Auburn University Montgomery, said he would have opposed the change for much of his career, but he began using “slave” during public readings and found audiences more accepting. He decided to pursue the revised edition after middle school and high school teachers lamented they could no longer assign the books.

Gribben conceded the edited text loses some of the caustic sting but said: “I want to provide an option for teachers and other people not comfortable with 219 instances of that word.” … Gribben knows he won’t change the minds of his critics, but he’s eager to see how the book will be received by schools rather than university scholars. “We’ll just let the readers decide,” he said.

“This painted child of dirt that sticks and stings …,” Lee Ricketts, superstition is all we have left (blog):

My overall view would be that if the books have been excluded from schools because of the slurs, it is rather the case that they have been excluded because of bad, lazy teaching. … If schools are prepared to rather just ban something as important as great works of literature rather than teach them in a way that puts them in context – something that is surely required to educate anyway – then there is something fundamentally wrong with the direction education has taken. You cannot and should not airbrush history. However ugly or uncomfortable, history must be faced.

… I wouldn’t have the first clue as to what Mr Twain would have made of it, but I would hope that he would acknowledge something that has been lost in all the fuss around these new versions -– that is his original texts shall not be erased entire, that these changes pertain to one version only. For a random example, when The Rolling Stones changed the words to “Let’s Spend The Night Together†to “Let’s Spend Some Time Together†for an American TV show, the original version of the song didn’t vanish, after all, and the result was that the song was heard by as wide an audience as possible.

One thing I do take offence to in regards of this whole matter is the comments made about Alan Gribben. Many people have labelled him as “stupid,†“crazy†and several other slurs which question his sanity and intelligence. He is a man with a great passion for literature in general and Mark Twain in specific, and is doing everything he possibly can to expose his works to as wide an audience as possible. One suspects he expected such a backlash but pushed ahead anyway. As far as I can see, looking at the wider picture, he deserves a great deal of credit for his actions, not the widespread vilification he is getting.

“Controversial Changes to Public Domain Works,” Christopher Parsons, Technology, Thoughts, and Trinkets:

… In the case of NewSouth, however, we’re dealing with a localized, particular, non-uniform transformation. There is a change to the words of the text but this doesn’t have the same qualitative impact as an all-out uniform and unquestionable modification. NewSouth should be encouraged for doing something daring with a public domain work.

This said, encouraging transformative uses doesn’t mean that we accept changes without question; we need to seriously and critically interrogate the modifications. What is important, however, is that we not prevent those changes: part of authorship and being an engaged citizenry is critically engaging with the way cultural artifacts are produced and disseminated. The ire raised by NewSouth indicates that we’re dealing with a transformation that is inciting members of society to talk about issues of truth, culture, history, racism, and so forth.

These are incredibly important issues, and it’s a good thing to have discussions about them as members of a (hyper)literate society. Transformation of works is to be encouraged, and it’s something that’s often discouraged by contemporary instantiations of copyright – this is one of the key ways that copyright works to stiffle and muffle free speech …

“Voices: The Huckleberry Finn Controversy,” compiled by Arturo R. GarcÃa, Racialicious:

The idea that we can somehow make any of these cultural products clean and nice is foolish. The whole point of culture and of literature is to challenge us.

— Professor Melissa Harris-Perry, associate professor of Politics and African-American Studies, Princeton University.

For a single word to form a barrier, it seems such an unnecessary state of affairs.

— Alan Gribben, editor, Mark Twain’s Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn: The NewSouth Edition.

“Hipster Huckleberry Finn Solves Censorship Debate By Replacing ‘N-Word’ With ‘H-Word,” The Village Voice:

Richard Grayson, a Brooklyn writer and editor, has gone above and beyond angry or satirical tweets in response to [NewSouth Books’s] announcement that they would release version of Huckleberry Finn (and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer) without the word “nigger.” He’s released a whole new version of the book, entitled The Hipster Huckleberry Finn, which replaces every instance of the offending word with “hipster.” Seriously.

If you’ve been moved by the ongoing debate and you have children in school, solicit a list of what books they’ll be reading this year, and if no often-banned books appear on the list, encourage your child’s school to assign one (of the often-banned books like Catcher in the Rye, The Color Purple, or Huckleberry Finn as part of the curriculum). We invite you to purchase a copy of Huckleberry Finn in whatever edition pleases you, read it to your children if you’re so inclined, and help change Huckleberry Finn‘s status as the fifth most banned school book in the country. We hope everyone takes this as an opportunity to rediscover the pleasures of reading Mark Twain.