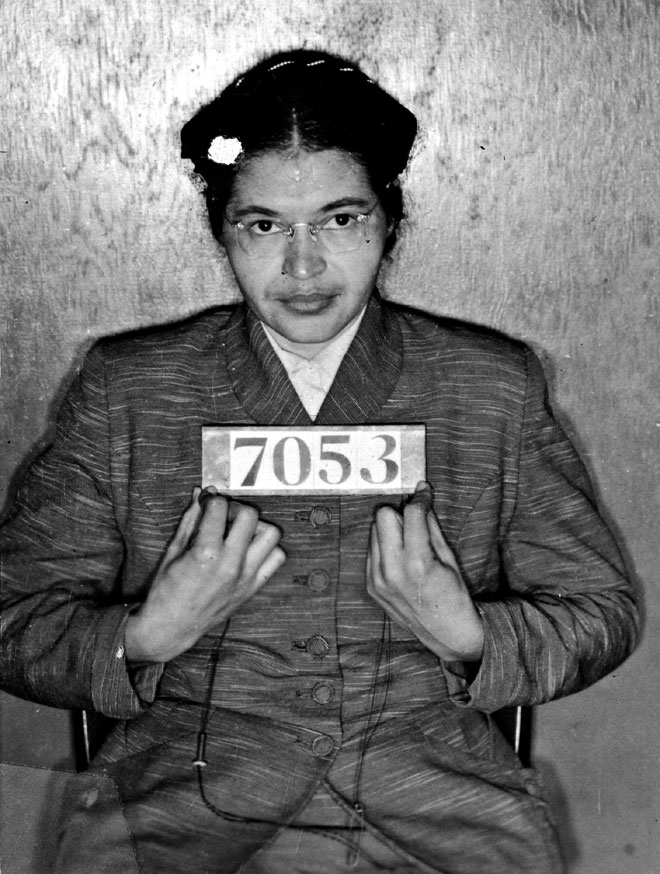

Sheriff’s booking photo of Rosa Parks (Associated Press)

Today, November 13, in 1956 was Day 345 in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. It was also the day that the boycotters won victory in their struggle that began after the arrest of Rosa Parks on December 1, 1955. The boycott began four days later, on December 5, 1955, on the morning of the day that she was to be tried in Montgomery city court on misdemeanor charges of violating the city law that said that blacks and whites had to sit in segregated sections on local buses.

She was tried and was convicted and fined $10 and $4 in court costs. Her lawyer, Fred D. Gray, announced that he would appeal her case, which he did. But Mrs. Parks’s misdemeanor conviction was mooted when the U.S. Supreme Court on November 13, 1956, affirmed a lower-court decision that the Montgomery bus seating law was unconstitutional. That lower-court ruling, based on the principle established in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, was written by U.S. District Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. for a three-judge panel consisting of himself and U.S. Circuit Judges Richard Rives and Seybourne Lynne. Rives, a Montgomerian, concurred in Johnson’s opinion; Lynne, of Birmingham, dissented.

City and state officials in Montgomery refused to accept Johnson’s ruling and appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Because the case involved a constitutional conflict between state and federal law, it was a direct appeal to the Supreme Court without passing first through the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals; that was also why the original case was heard by a three-judge panel rather than by Johnson alone.

Alabama Attorney General John Patterson and Montgomery City Attorney Walter Knabe represented the City of Montgomery. Fred Gray, Thurgood Marshall and Robert Carter of the national NAACP, and Charles Langford, the only other black lawyer in Montgomery besides Gray at the time, represented the plaintiffs.

The plaintiffs, by the way, did not include Rosa Parks. Gray had decided her criminal case needed to be kept separate from the civil lawsuit against the segregation laws themselves. So the four black women who became Fred Gray’s clients and actually sued the city were Aurelia Browder, Susie McDonald, Claudette Colvin, and Mary Louise Smith — all had been previously arrested and convicted on the same charge as Mrs. Parks.

The Supreme Court did not hear Montgomery’s appeal; it simply affirmed, on the basis of the lower-court record and the briefs in the case, the lower court’s ruling.

News of the Supreme Court decision reached Montgomery instantly, but the City of Montgomery, intransigent to the end, did not immediately end the segregated bus seating. That moment did not come for another month until the Supreme Court order was printed, mailed, and received at the Federal Courthouse in Montgomery on December 20, 1956, and formally served by U.S. marshals on the city officials. And then on the morning of December 21, 1956, 382 days after they had begun boycotting, Montgomery’s black citizens returned to the city buses with the right to sit wherever they pleased and to be treated with the same dignity and courtesy as white passengers. Which was all they had wanted in the first place.

There are many ironies in the Montgomery Bus Boycott. The Judge John B. Scott Sr. who convicted Rosa Parks was the grandson of one of Montgomery’s founders. He was also the secretary of the local bar association and had administered Fred Gray’s bar exam in 1954, admitting the young black lawyer to legal practice in Alabama. Attorney General John Patterson would parlay his segregationist stance in the bus boycott and other cases into election as Alabama governor in 1958 (beating a young George Wallace, who was the liberal in the race). Patterson’s election and Wallace’s conversion to segregationist tactics to win the governor’s office in 1962 set Alabama on the path toward full resistance to civil rights progress.

Ultimately Wallace and Patterson both recanted their segregationist views and policies and apologized, but by then Alabama had already lost in every court it ventured into, and Rosa Parks and Fred Gray were both national heroes, along with Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph D. Abernathy, just to name two of the boycott participants; there were hundreds of others who played vital roles but never gained national fame.

And the 382 days . . . for years history books and even the Smithsonian Institution stated that the boycott lasted 381 days. But when they did the math, they forgot that 1956 was a leap year, and adding February 29 makes it 382 days.

[NewSouth Books titles exploring this history include: Bus Ride to Justice by Fred D. Gray; The Judge by Frank Sikora (biography of Frank M. Johnson Jr.); A White Preacher’s Message by Robert S. Graetz (original member of the Montgomery Improvement Association); This Day in Civil Rights History by Ben Beard and Randall Williams; Jim Crow and Me by Solomon S. Seay Jr.; Nobody But the People by Warren Trest (biography of John Patterson); Johnnie by Randall Williams (children’s book about Rosa Parks’s friend, Johnnie Carr), and Dixie Redux edited by Raymond Arsenault and Vernon Burton (an anthology containing a chapter on national reaction to the Montgomery boycott).]