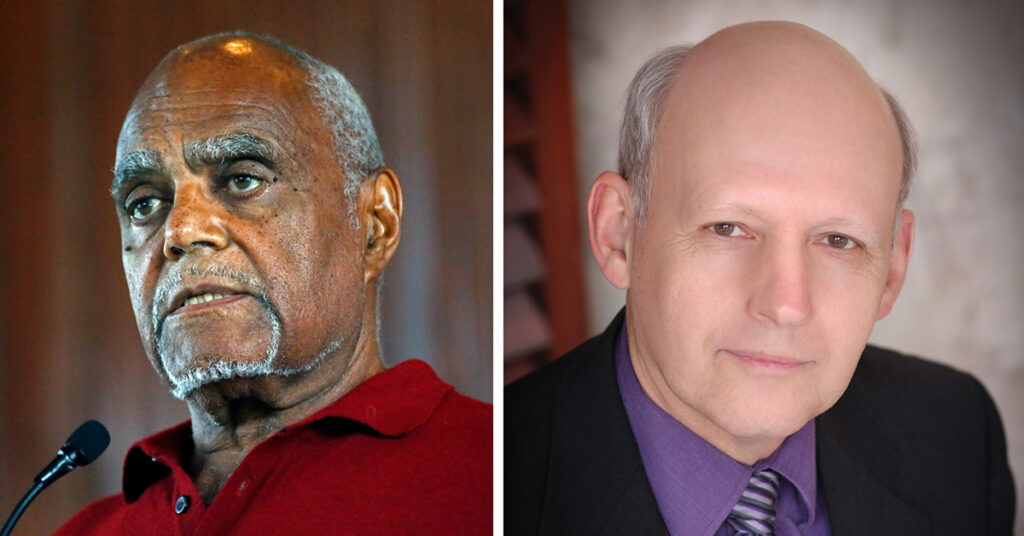

Bob Moses, one of the most courageous human beings to have walked this earth, died July 25, 2021. Tributes have been pouring in from many who knew Bob or knew of him, including President Barack Obama, who said: “Bob was a hero of mine. His quiet confidence helped shape the civil rights movement, and he inspired generations of young people looking to make a difference.â€

Bob was twenty-five and a school teacher in New York City when he became inspired by the bravery of the young women and men who started the sit-ins in Greensboro, North Carolina, in February 1960 that quickly spread throughout the South. In the summer of 1960, Bob headed South intending to work with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. Instead, he became involved with the fledgling Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and was encouraged by Ella Baker to go to Mississippi to determine how this largely student-based group could break down the barriers for equal rights for Black Mississippians, then living in a totalitarian, white supremacist state.

After his initial foray into Mississippi, Bob returned to the state in the summer of 1961 to build upon the nascent civil rights activism of Medgar Evers and others. Bob led a voter registration drive in McComb, one of the most repressive cities in a very repressive state. He was soon joined by young Black Mississippians Hollis Watkins, Curtis Hayes, Brenda Travis, and others, who saw in Bob and his mission the opportunity to create real change in their lives and the lives of Black Mississippians generally. Bob and his allies were met with bombings, beatings, jailings, and killings. While the initial civil rights beachhead in McComb was frustrated by the white power structure, the movement persisted.

Over the next four years, Bob continued the movement with voter registration drives and direct action throughout Mississippi. Although Bob was often described as the “leader†of the Mississippi movement, he shunned titles. His approach and the approach of SNCC generally was to encourage and empower local Black women and men, such as Fannie Lou Hamer, to lead the movement in their communities. As he often stated, quoting from the Constitution, “We the People, have the power, not the presidents, the senators or the congressmen, and we must seize that power that was given us by the Founding Fathers.â€

In the push to bring about meaningful change in Mississippi, Bob championed the 1964 Freedom Summer project that brought large groups of students, many of them white, to work with Black Mississippians to achieve their rights. Much of what they worked for came to fruition with the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. While all was not successful, it was partly through Bob’s efforts that today Mississippi has more Black elected officials than any other state.

Bob never ceased in his efforts to empower Black men and women. With the assistance of a McArthur Genius Grant in the 1980s, he guided the formation of the Algebra Project, teaching math literacy in inner-city schools in Mississippi and elsewhere. Bob’s roots as a teacher made him see that if Black youth were to succeed in this society, they needed the necessary math skills to compete. Many young African-American women and men who might not otherwise have been able to obtain a college education were able to do so as a result of this program.

Bob remained ever optimistic despite the obstacles he encountered in Mississippi and the more recent obstacles to voting rights. He encouraged some of his former compatriots in the telling of their stories by writing forewords to their books, including two published by NewSouth, Brenda Travis’s Mississippi’s Exiled Daughter and Gwen Patton’s My Race to Freedom. In the foreword to Patton’s book, he described her as a person “with dedication, principle, and an unbending devotion to justice, equality, and the well-being of all people.†These powerful words of Bob Moses equally describe him and his own life mission. He will be sorely missed.

John Obee, inspired by Bob Moses, worked as a civil rights worker in Mississippi in 1967 and has continued his civil rights activism since that time. He is currently working on a project to increase minority representation in the labor arbitration field. Obee is the co-author of Mississippi’s Exiled Daughter, the memoir from civil rights activist Brenda Travis.